Kevlar® cloak uses chlorine chemistry for military advantage

Avoiding detection by thermal cameras, known as infrared stealth, is vital for the military. Yet, effectively hiding targets is a major challenge, since neither camouflage nor darkness can hide heat-releasing objects from thermal cameras, writes Chemical & Engineering News. In a promising new development described in ACS Nano[1], Kevlar® – made using chlorine chemistry – has been used in a strong, lightweight and foldable cloak that can make objects invisible to infrared cameras. This is effective across a range of temperatures, and without the need for added energy.

The Kevlar-based cloak performs better than other infrared stealth materials due to a combination of excellent thermal insulation and ultralow infrared transmittance, say the researchers. The material is a thin, spongy sheet made of Kevlar nanofibers drenched in polyethylene glycol, writes C&EN; “polyethylene glycol [PEG] is a phase-change material that softens when heated, shifting from a crystalline to an amorphous form. The PEG captures the energy of infrared emissions and then releases that energy as it re-hardens, without changing temperature.” Senior author Xuetong Zhang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Suzhou Institute of Nanotech and Nanobionics, is quoted as saying that clothes or helmets could be lined with the material to provide infrared stealth.

All objects emit thermal energy at infrared wavelengths that depend on their temperature. A practical thermal cover needs to tune these infrared emissions to match the thermal color of the environment, which can vary by place, season, and time of day. Earlier efforts to make stealth screens have involved materials that actively suppress thermal emissions; these materials consume energy, work in a narrow range of temperatures, change color too slowly, or are rigid.

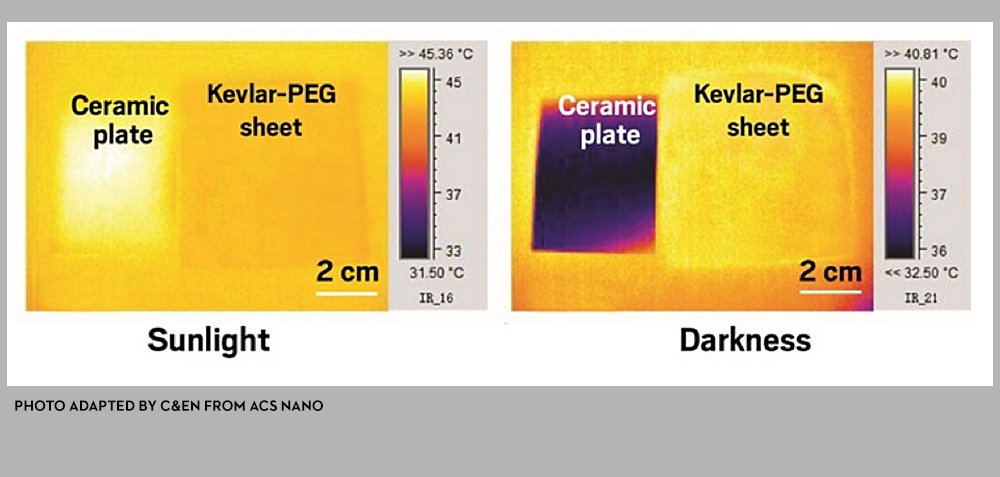

To test the new cloak’s ability to hide objects in daytime, the scientists shined simulated sunlight onto a ceramic plate, and used a thermal camera to take photos with the light on or off. The plate heated up and cooled down more quickly than its surroundings, making it clearly visible in thermal images when uncovered. “When the researchers draped the Kevlar-PEG sheet over the plate, however, it disappeared because the PEG absorbs and releases infrared emissions more slowly and blends into the background,” says the newsletter.

Bringing this technology to scale will not be without challenges, including the fact that the methods used to make the Kevlar nanofiber film might not be suitable for manufacturing large quantities, costs may be high, and the film might not be resistant to extreme weather.

[1] Further permissions related to the material excerpted should be directed to the ACS